I can’t think of a more inspiring NYC institution than the New York Public Library. It’s still rich with the unnecessary spatial trappings that are often too costly to be included in today’s buildings (with the possible exception of the new Calatrava extravaganza downtown). I like to think that the grand staircases outside and in, elaborate lobby spaces, murals, and inevitable sense of ceremony impact even those serious folks who labor daily in the glorious Rose Reading Room or in one of the less majestic study rooms. All those amenities may not address the NYPL’s main raison d’être, but I find them a lure even though I’m not a regular researcher any more. And a recent visit reminded me of the various anti-institutional protest movements of the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, which ranted not only against cultural elitism and workers rights, but also about the off-putting architecture of museums, with their classical facades and elaborately-staired approaches. That puzzled me since, growing up near what was then Buffalo’s Albright Art Gallery — with its elegant Greek revival building, designed by Edward B. Green for the 1901 Pan-American Exposition (but not opened until 1905) — I always delighted in the sense of going to a special place for a special experience; not off-putting to me! In those days one walked up lots of stairs (not quite Rocky’s climb at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, but nevertheless awesome for an impressionable child); that was before Gordon Bunshaft’s now-iconic, International Style, 1962 addition made entering more practical, if also more banal.

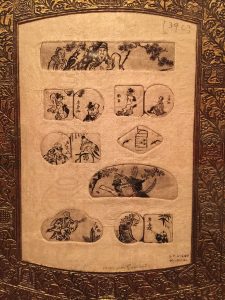

I remember that feeling of uplift every time I wander into the NYPL, as I did to view the strange, but fascinating current exhibition, A Curious Hand: The Prints of Henri-Charles Guérard (1846-1897). Not on my radar screen, Guérard turns out to be a masterful printmaker both for technical prowess and for the range of his visual interests. Working to help Manet with his own prints, and producing copies of etchings by famous predecessors such as Rembrandt, Guérard’s main interest for me is the range of bizarre, occasionally kinky (not sexual!) imagery. He plays with Japonisme influenced by Hokusai.

He channels Poe, who had recently been translated by Mallarmé, in one of the show’s most impressive images.  .

.

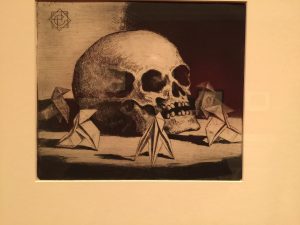

He puzzles with inexplicable, but exquisitely-executed, grotesqueries: who knows what a skull has to do with origami?  I’m not sure you come away from the exhibition with a clear understanding of what this guy was all about, but for sheer visual and technical delight, it’s worth a visit. And you get to experience that great building to boot!

I’m not sure you come away from the exhibition with a clear understanding of what this guy was all about, but for sheer visual and technical delight, it’s worth a visit. And you get to experience that great building to boot!

And it’s a short walk from the NYPL to the Morgan Library and Museum. Changing its name a few years ago — presumably because being a library wasn’t sexy enough, and the Morgan folks hadn’t heard that museums are (citing a young Renzo Piano, long before he screwed up the Morgan’s architectural ensemble) “dreary, dusty and esoteric institutions” — it’s still one of the most wonderful islands of pleasure on Manhattan Island. It’s also where one always stretches one’s concept of visual pleasure, no more so than with the current Emily Dickinson exhibition, I’m Nobody! Who are you? You can really get sucked into the glories of her penmanship and a few (not enough!) poems in her hand. I was relieved to find one of my childhood favorites:

“I heard a Fly buzz — when I died –” And here one also sees Dickinson less as the famous recluse of our collective mythologies and more as someone engaged with others.

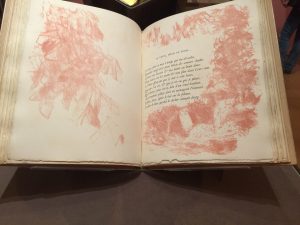

A small exhibition in the Morgan’s Thaw Gallery, Delirium: The Art of the Symbolist Book is interesting for somehow drawing together a range of imaginations that connect Guérard and Dickinson with the Symbolists here, among whom are writers and artists Charles Baudelaire, Stephane Mallarmé, Paul Verlaine, Alfred Jarry, Maurice Maeterlinck, Odilon Redon, Maurice Denis, Pierre Bonnard, Henri Fantin-Latour, Henry van de Velde, and Fernand Khnopff. I noticed a book (Les Vierges illustrated by József Rippl-Rónai) by Belgian writer, George Rodenbach (1855-98), whose compelling short Symbolist novel, Bruges-la-Morte, I discovered after it had been featured in one of the WSJ’s weekly Masterpiece features a few years ago. It was also fun to see Paul Verlaine’s Parallelèment (1900) “considered to be the first modern artist’s book” illustrated by Pierre Bonnard, in its deluxe edition All these years I thought my fancy little edition of the book was deluxe; I guess not.

So what’s a library and what’s a museum? Who the hell cares?

whom I’ve nominated to play

whom I’ve nominated to play  if they ever make a movie out of the

if they ever make a movie out of the