Last year (2018) it was Tintoretto-time (everywhere) along with the joy of having every Rembrandt in the Rijksmuseum‘s collection on view in Amsterdam. Mr. T managed a few self-portraits,

but they don’t begin to express the wonder of his works (of which, for me, the high point has long been the great Crucifixion (1565) at San Rocco in Venice).

Mr. R (Mr. R v. R?), on the other hand, depicted himself at many stages of his life, so that he gains a personality (albeit often enigmatic), that provides us with the illusion that we know him, and not just

his work. Rembrandt looking at himself set the standard for all the artists who followed: a high bar. I can’t imagine being an artist trying to address that.

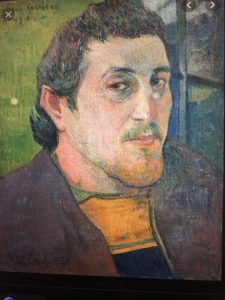

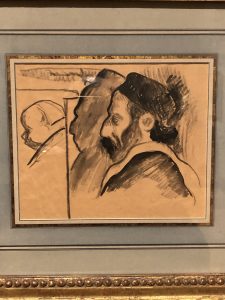

It was difficult to avoid such thoughts viewing three wholly disparate exhibition concurrently on view in London, all of which display self-portraits. At the National Gallery, a beautiful Gauguin portrait exhibition begins with a gallery of self-portraits, and while several are compelling, one gets a series of images of the artist without gaining any insights into him as a person; he appears to depict himself more as a visual fact than as a personality.

That’s OK, given Gauguin’s especially interesting facial features: prominent nose, moustache, and eyes that manage to avoid telling us too much. That they were probably “bedroom eyes” — especially during his time in Tahiti — has generated bits of controversy in the #MeToo age, and the National Gallery tries (perhaps too hard?) to address this in the wall panels.

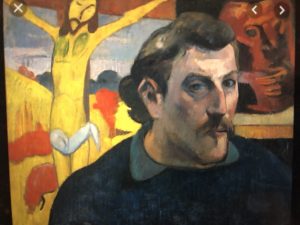

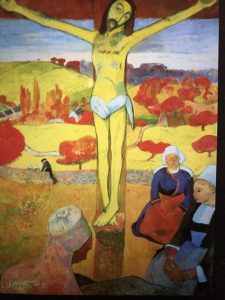

My favorite self-portrait is (of course) the one with the Yellow Christ in the background, since it reminded me of my favorite work in the Albright-Knox Art Gallery (below, 1889) when I was growing up in Buffalo.

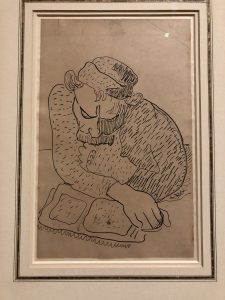

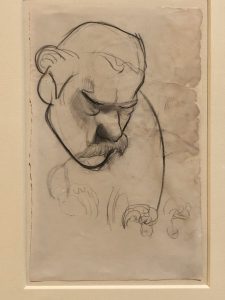

Despite the artist’s clear interest in looking at himself, I found the most compelling portraits in the exhibition to be those of Gauguin’s friend and artist-colleague, Meyer de Haan, about whom I have written in the past.

Indeed, the Gauguin paintings seem to gain their beauty more from the artist’s palette than from his helping us enter into the sitters’ personalities, as is especially evident in another of my favorites, this gorgeous work (Vahine no te vi – Woman of the Mango, 1896) from the Cone Collection at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

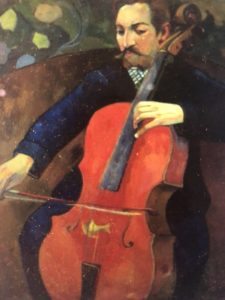

And since I have always been a cello groupie, I was disappointed that the Gauguin portraits exhibition in London didn’t include a work – Upaupa Schneklud (The Player Schneklud, 1894) — that I helped bring to the Baltimore Museum of Art.

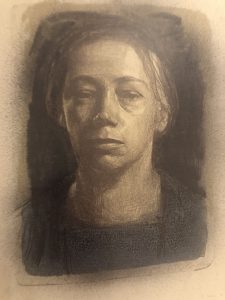

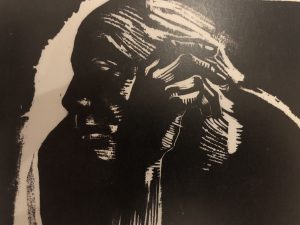

The Käthe Kollwitz exhibition now at the British Museum is sublimely beautiful, and a wall of self-portraits, from varying periods of her life, seems to show us a visually unchanging person. In her photograph, Kollwitz was evidently a plain woman, emphatically eschewing any suggestions of feminine glamour or allure; nevertheless there’s something compelling about her. Presumably that’s both a reflection on her politics (the exhibition in general conveys her commitment to political issues) and a true reflection of how she looked (or presented herself), if one is to judge from the one photograph on view, which accords completely with how Kollwitz saw herself. “Just the facts, ma’am” – as Sgt. Joe Friday use to say on Dragnet.

In her self-portraits Kollwitz seems always to look a great deal like her photographic image: dour and concerned — the latter certainly true if we are to judge by the array of politically-based themes in her work. They constitute most of the exhibition, some of it already familiar to Kollwitz aficionados.

On the other hand, the exhibition of work by Helene Schjerfbeck, at the Royal Academy provides us with a serious revelation, and is perhaps the most interesting of the many shows currently on view in London. The trajectory of Schjerfbeck’s life (1862-1946) intersects with many critical moments in art history of the last century. But she only mirrors those very occasionally, creating an oeuvre that is often breathtaking and generally distinctive. I am reminded of so many conversations with curators and dealers years ago (albeit not recently; since I don’t engage in that sort of discourse much anymore): the fictional idea that if an artist is really “good” and “worth seeing” then he/she (usually he) will somehow “emerge” from the morass of art out there. We know that’s not true, since “rediscoveries” are always taking place (the most famous, perhaps, being the emergence of Vermeer as a distinct artist in the late 18th and then 19th century) – albeit these days they tend to be generated by commercial opportunities.

As a Finnish artist and a woman Schjerfbeck was evidently of minimal interest to mainstream art historians concerned with art of her time, despite her having studied and shown in Paris, lived in England (especially Cornwall), and traveled extensively. In 1939 an exhibition of her works in there USA was cancelled following the outbreak of World War II. So she can’t have been entirely under the radar screen. The number of stunningly beautiful paintings in the RA’s exhibition reminds us once again of how narrow “mainstream” art interests have always been. We see hints of Degas and Cézanne and Sargent , but also of 17th century genre painting.

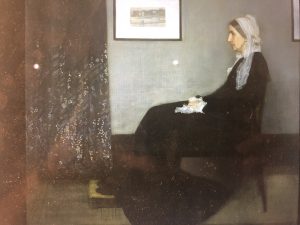

Elsewhere there are adaptations from El Greco paintings, and it’s difficult to miss the direct reference to Whistler’s Mother (1871) in her 1909 painting of the artist’s mother, which has very different strengths from those of the more famous work..

We experienced that false (?) sense of discovery in New York when Hilla af Klint (another “unknown” Scandinavian woman) turned out to be one of the most popular recent exhibitions at the Guggenheim Museum, although in her case a lot of the excitement seemed to revolve around “discovering” an artist who shattered the academic chronologies about the development of geometric abstraction. That visitor numbers swelled for that exhibition may tell us something about the possibilities of showing work by artists “of whom no one has ever heard.”

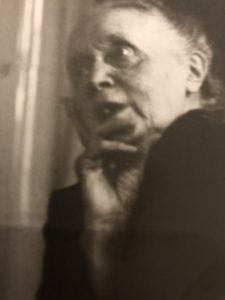

Late photographs of Schjerfbeck (1935 and 1945)

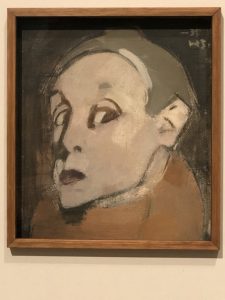

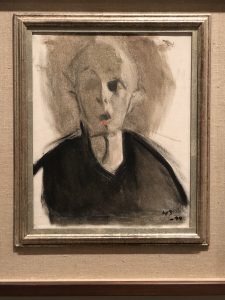

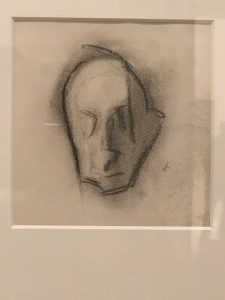

have an eerie (presumably unintentional) affinity to the Kollwitz self-portraits. Nevertheless, having seen how both Gauguin and Kollwitz focus on themselves, Schjerfbeck’s self-portraits are in a wholly different category. She doesn’t track herself the way Rembrandt did, with his gorgeous and elaborate paintings that nevertheless let us in on his sense of aging. Rather, one gallery of this exhibition shows us the artist from her youth as a typical young woman of the era (1884-85), and she moves from seeing herself as a whole — even wholesome — person (i.e., hair, skin, clothing) to what evolves

into to be an obsessive interest in understanding what happens to facial features in the aging process, without Rembrandt’s bells and whistles.. It’s an awesome series of images in which we watch her

observing herself age — with no self-pity, just ruthless observation. She’s clearly not emotionally detached from seeing herself; yet it’s difficult to tease apart the artist’s emotions as conveyed in these self-portraits.

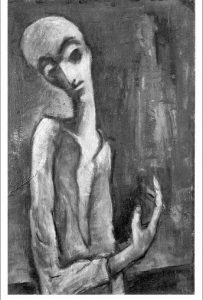

And in her Last Self-Portrait (1945) we watch Helene Schjerfbeck turn into a spectre that resonates in

strange ways — and given the dates, in odd contemporaneity — with drawings of the muselmann type of Holocaust concentration camp victim portrayed by several artists, as for example this one by Yehuda Bacon (b. 1929).  Nevertheless, the Schjerfbeck exhibition at the Royal Academy provides us with the excitement that comes from once again challenging and expanding the canon. Let’s hope we see more museums willing to take these risks.

Nevertheless, the Schjerfbeck exhibition at the Royal Academy provides us with the excitement that comes from once again challenging and expanding the canon. Let’s hope we see more museums willing to take these risks.

,

, interesting. And one wonders whether either artist ever encountered the wonderfully concise MirrAnd oneored Room (1966) by Lucas Samaras (

interesting. And one wonders whether either artist ever encountered the wonderfully concise MirrAnd oneored Room (1966) by Lucas Samaras (

breaking Lumia works, which he began as early as 1919, and which were the subject of a compelling recent (2017)

breaking Lumia works, which he began as early as 1919, and which were the subject of a compelling recent (2017)