I’ve never been an avid user of audio tours, although I recognize their utility for many museum visitors. So having them available on my smartphone doesn’t do much for me. (And on the few occasions when I wanted to check out what was being said, I’ve often found the museum’s wifi signal too weak.) But often I do like to take photos of interesting works, or close-ups (or enlargements) of something that fascinates me. On the other hand, I was impressed that the Prado doesn’t permit photographs in the galleries. That makes it possible to view revered works (e.g., Las Meninas) free of enthusiastic selfie-takers. And for the intrepid viewer, there are ways to calculate the guard’s path, so that it’s possible to work surreptitiously while the guard is making his/her rounds (albeit not in front of Las Meninas). More about that later on.

The smartphone is my steady friend for helping me check on visual relationships that I think might be evident — while also reminding me that my visual memory might not be all that I assumed it was. So even while passing a Bond Street shop (Pronovias), a dress (below, left) in the window caught my eye because I thought I had recently seen it (below, right) somewhere (at the Met Cloisters segment of Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination).

My phone helped me check my memory!

I’m not certain why I found myself fixated on the depiction of linen in a pair of paintings, hanging side-by-side (for easy comparison) by Andrea Mantegna (ca. 1454) (below, left) and Giovanni Bellini (ca. 1470) (below, right) in the splendid eponymous exhibition of their work currently at London’s National Gallery.

But there I was, a few days later, at the Royal Academy, trying to figure out the amazing early 16th century copy of Leonardo’s Last Supper,

which has until recently not been on view. I was struck by the linen tablecloth and wondering how closely it might relate to the swaddling cloths on the Chirst child in the two Presentation of Christ in the Temple I had just seen.

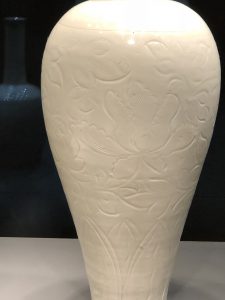

Not as close as I imagined, but the phone photo was a great way to check it out. And a couple of days later the swaddled Christ child image came back to me when I saw a white Meiping (plum-blossom) vase among the British Museum’s vast Chinese ceramics displays.

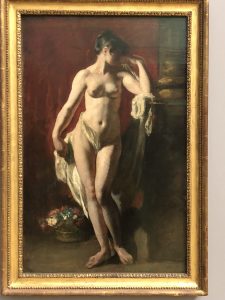

Yes, I know they have nothing to do with each other, but thanks to my phone I could check out what I thought I remembered. This keeps happening — surely not only to me — and I relish the opportunity to check out my [perhaps failing] memory, as when I saw William Etty’s Standing Female Nude (1835-40) at the Tate Britain (below, left), and was sure that Thomas Eakins’ study (below, right), William Rush’s Model (1908) was similar (or a ripoff). Wrong again! Because it’s a study (one of several) of a front-facing nude, very different from the 1876-77 version in Eakins’ famous William Rush Carving His Allegorical Figure of the Schuylkill River.

The proximity of those visuals dancing in my head also changed the way I looked at the wonderful Roman 2nd century AD marble Venus I encountered at the British Museum a day later. Checking out photos stored on my phone expands the experience enormously!

A Mantegna drawing, Three Studies for the Dead Christ (ca. 1455-65) (below, left) in the National Gallery show brought to mind the artist’s dramatic and (for me) memorable, highly-foreshortened The Dead Christ and Three Mourners (1470-74) (below, right) now in Milan’s Pinacoteca Brera. I was certain the drawing was similar to the painting; but the ability to access the photo of the Milan painting while in the London gallery looking at the drawing helped me see the differences. Exciting!

The phone camera’s zoom ability often assists in viewing things that are simply not otherwise visible. For example, in a current British Museum exhibition, I was able to photograph close-up details that I really couldn’t see in the exhibition cases, although they were diagrammed on the accompanying labels.

Thomas Spence (1750-1814) was an English radical who defaced coins, as this one attacking Prime Minister William Pitt. My phone helped me see it!

As it also did this 1897 anti-papist British one-penny coin.

As for my having fun tracking the guards at the Prado, I close this blog by sharing my “purloined” photos from Room 56A. I was mesmerized by Bosch’s Adoration of the Magi triptych (1494), despite the big crowds that were focused on Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights (1490-1510) across the room. Managing the crowds at the more popular painting is a serious task for the gallery guards. Far fewer people pay attention to the Adoration, which was the painting that really captured me. Still, I was unable to get a full sense of the finer details — the gold gifts being presented to the Christ Child, the wonderful scenes embroidered on the robes, the men on the roof. Here’s where my camera would help — but not with guards around. So I spent a lot of time watching the security path, figuring out when I could capture closeups (“Alright, Mr.Bosch, I’m ready for my closeup!”).

Now, thanks to a guard that maintained a predictable routine march through the gallery, I could really check on the details that help make this painting so amazing, whenever the guard wasn’t nearby.

I like to think I wasn’t bothering anyone by breaking the rules. (That’s what they always say…..) And I’m hoping that museum wifi systems continue to improve, so that we can expand our uses of increasingly helpful cellphones.