PRODIGAL SON

Contemplating Simone Martini’s Christ Discovered in the Temple

(published, with illustrations, in Jewish Quarterly, London, Fall 2004)

American boys of my generation (and earlier ones) grew up in the firm belief that anyone could be president. We had gone from FDR to HST to Ike, so the opportunities appeared reasonably open. But not for me. I was born in Germany, and only a “natural born citizen…shall be eligible to the office of president” (as our Constitution puts it). I wasn’t certain of the precise language, but I was always aware of that one limitation in my career options.

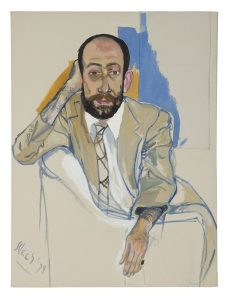

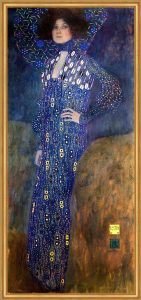

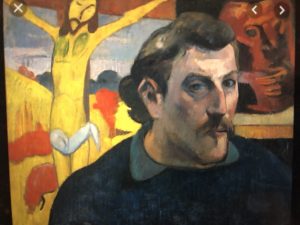

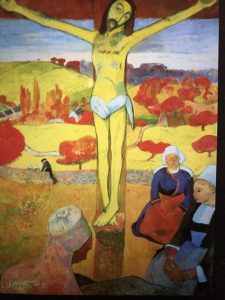

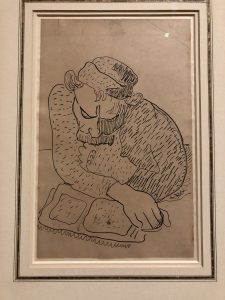

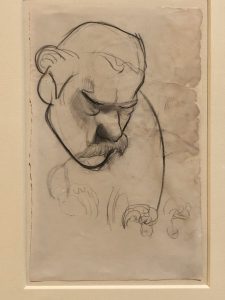

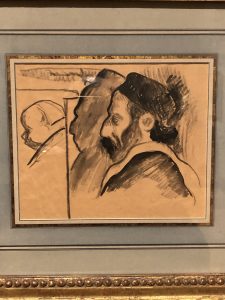

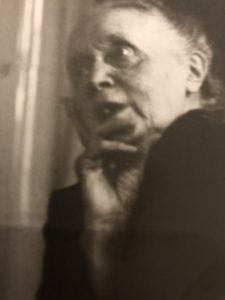

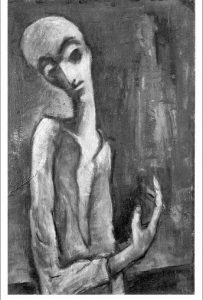

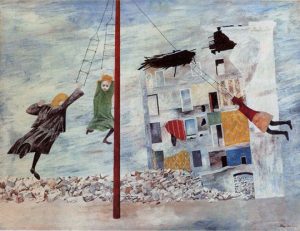

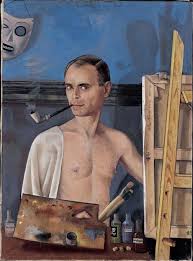

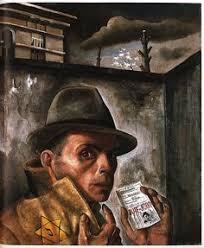

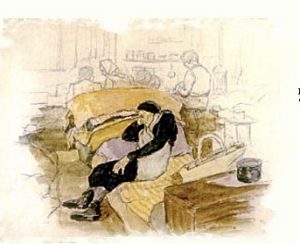

I did, however, go through a brief Jesus fantasy. It was in 1978, during one of several sittings for Alice Neel, who painted a wonderful portrait of me. (No thanks to me or to that portrait, her soaring reputation has put my canvas likeness far out of my reach financially.) Aside from the feeling of privilege that this extraordinary painter had asked me to sit for her, part of the fun was hanging out with such an outspoken and outrageous lady. She was then in her late 70’s, as nimble mentally as she was physically, enjoying a surge in her career that also loaded her with iconic status in the women’s movement. I recall sitting patiently still, looking out of her strategically-placed corner window at 107th Street and Broadway, discussing Edmund Wilson’s Memoirs of Hecate County, which I was reading at the time. I was astounded that Alice remembered all the details of the story, almost quizzing me, although she said she had only read it once, when it was first published: 1946, I confirmed in my paperback. Studying my bearded face, as she painted and we talked seriously, Alice suddenly decided that she should paint me in a Crucifixion. It was a subject she had never painted; it was about time; and she told me she was inspired by my Talmudic look, which would make me an appropriate model for Jesus. Besides, she said it was important that the model be Jewish; we had discussed the Holocaust and her prescient 1936 painting, “Nazis Murder Jews” – a subject of no interest when she painted it.

“Would you really do that?” my father asked, when I told him about this exciting opportunity. “Why not? She’s an artist I admire a lot,” I replied. I had minor misgivings that someone might look at the painting and say, “hey, I know that guy!” But other than that, I was comfortable with the idea. So Alice and I carried on intermittent conversations for some months, trying to make dates for a sitting. I would have to travel up from Washington, she was increasingly invited to speak all over the country, but by the time of her 80th birthday celebration (in Charles Stewart Mott’s expansive Fifth Avenue penthouse) she was still serious about fitting this project into what had become the life of an art celebrity. Meanwhile, given Alice’s famous portraits of people in various stages of dress (although my portrait has me in a suit), I was contemplating what I would (or wouldn’t) be wearing while hanging from the Cross. I knew I wasn’t going to be suffering the physical pains that must have beset F. Holland Day, when he put himself in Jesus’ place for photography’s sake (this was long before Mel Gibson’s vulgarities). And I was amused at the notion of a loincloth or jockey shorts or boxer shorts or a robe or whatever Alice might have in mind, which was never quite clear.

But then Alice Neel died after a bout with cancer (1984) and my Jesus daydreams died with her.

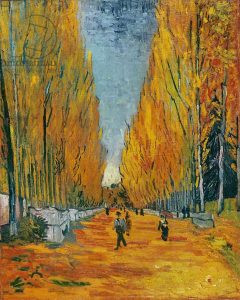

Until recently, when I saw Simone Martini’s extraordinary small masterpiece, Christ Discovered in the Temple (1342, Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool). My Jesus fantasies returned, even before I read one of the thoughtful wall texts that said “he depicts a human drama with which we can still identify today.” Here is a work that demands scrutiny while directing the viewer’s thoughts down very personal and possibly even awkward paths.

My father wasn’t a carpenter, although the family business in Berlin was lumber and veneers. As far as what I can tell from my mother’s quite frank discussions of her youth, she wasn’t a virgin. My older brother carried a not-entirely-unjustified resentment, feeling that our parents treated me as if I were a gift from God. But that’s not why I feel so at one with the young Jesus whom Simone Martini shows us confronting his parents. They have discovered him hanging out, and they are none too happy. We have each been discovered – somehow, somewhere – forced to face parental wrath. Think of poor Euan Blair a few years ago, having to confront his folks after a night out in Leicester Square; or the Bush twins caught for underage drinking. Think of the teenager running off to meet someone he or she has met on the internet. That sense of horror and embarrassment at being caught works on both sides of the equation: the catcher and the caught both having to come to terms with how they relate to each other.

So why do I identify with this extraordinary painting? I was about to turn 20, finishing my third year of university, and had gone off from Boston to San Francisco for my grandmother’s 80th birthday. Cadging a ride west with a fellow student had been relatively simple. And as instructed by my concerned parents, I dutifully telephoned them every night to tell them I was safe. But to find a ride back (I need to return quickly for my summer job) turned out to be more complicated, requiring me to scour the adverts in San Francisco newspapers. That eventually yielded me a driver, also in a hurry to get back east for a summer job, so we had to share driving, with a kind of steady rota of three passengers driving steady, night and day, barely stopping for food and petrol. So I forgot to call home. Or did I forget? When I finally arrived, my parents were angry and silent and accusatory. How could I not have called, as we had agreed I would? (I didn’t remember agreeing; I just thought I was being a good son.) My parents told me that they had aged twenty years just from worrying during those two anxious days. They had even listed me with the police on an APB (all points bulletin) to have me located. I felt guilt and shame – and my own kind of anger. When I reminded my mother of this incident, shortly before her death at 93, telling her that, given the aging I had put her through in 1957, she was really 113, she growled at me that it still wasn’t funny. At least she didn’t tell me that I would understand once I had children, because my own sons were by then quite grown up.

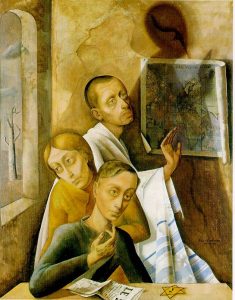

That’s what Simone Martini’s lovely little painting brings back to me. And much more. There are the complex reactions of parents disappointed in their son. “Son, why hast thou thus dealt with us?” is inscribed on the book, which sits in Mary’s lap – a quotation from Luke 2:48. (Jewish translation: “How could you do this to us!!”) Simone Martini’s parental pair engages in what would have been some sort of role reversal in my family. Truer to her ethnic roots, my mother more likely said “how could you do this to your father?” Here, Joseph points to Mary with a slightly angry, but mostly despairing, look on his face, as if to say, “Look what you’ve done to your mother!” This is emphasized by Joseph’s left hand protectively on his son’s shoulder, his right hand pointing at his wife. Mary is somewhat impassive (maybe she wasn’t really a Jewish mother), sad to find herself in this position, pointing to her husband, wishing she could figure out how to make excuses for her son. It’s a not unfamiliar game of parental ping-pong. They both also feel a sense of shame at having been placed in this position by their son. It’s frankly embarrassing. They are as angry at that indignity as they are at the actions of the lad.

Jesus, on the other hand, is not ashamed at having done wrong. Indeed, as far as he’s concerned, he has done no wrong. Jesus was spending time in the Temple toward a noble end that his parents couldn’t grasp: “Didn’t you know that I must be in my Father’s house? (Luke 2:49) He has his own ideas of what’s important, even if he’s only 12; they don’t entirely agree. They were worried about him. The artist makes clear that this is not simply a youth being scolded by his parents for wrongdoing. This is a standoff! Jesus is angry, his eyes almost cold. He affects a look that combines some slight sense of regret at disappointing his parents, with a strong feeling of chagrin at being hassled by them. Is he angry at being caught, or at feeling the injustice of their accusations? After all, he’s asserting his independence –”separating” is what we call it these days – and he seeks understanding, not reprimand. He has complicated feelings, as do his parents. This duality is familiar to most of us; we have been there. We recognize ourselves as children; we recognize ourselves as parents.

This wonderful small panel painting gives us a moment unfamiliar in an art tradition that gains most of its tender or grotesque insights from other elements in the life of Christ. The baby Jesus with the Virgin, in all their variant manifestations, generally presupposes a combination of maternal relationships with the overwhelming iconic status of the image itself. The multiple Passion scenes convey the pain and suffering which the devout are meant to re-experience as a devotional exercise. (“In every generation, it is incumbent on us to see ourselves as though we came out of Egypt.”) Simone Martini has given us a wholly different spin on the Holy Family. This painting, executed in 1342, when the Siennese painter was living in Avignon, is also rich in colour and compositional elements; yet it’s the emotive qualities that are most forceful.

The greatest works of art impress us not with the virtuosity of their technical qualities alone, even when we gasp at such, but with their ability to help us explore the inner feelings we all share. The artist as psychic archaeologist – or perhaps the artist as shrink – is an infinitely more powerful role than we are accustomed to ascribing to the creators of our museum’s most awesome wonders. I am grateful to Liverpool’s small masterpiece for helping to evoke, and even excavate, so many of these feelings.

Addendum (not published with this article):

Sometime in 1978 I was on a panel (or symposium) at the New School (while I was working at the NEA). After the program was over, someone came up to me and handed me a little scrap of paper (I may still have it) on which was written “I must paint you before I go to the happy hunting ground. Alice Neel.” So I asked the person which one was Alice Neel and she pointed out an old lady still sitting in the front row (people were leaving the room). So I went over to her and said something like “Wow! Did you really mean this?” and she said, gruffly, “I wouldn’t have written it if I didn’t.” So she said I should get in touch with her and she gave me her phone number. (We were living in Baltimore; I was working in Washington.)

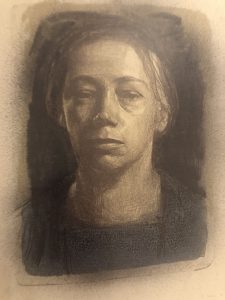

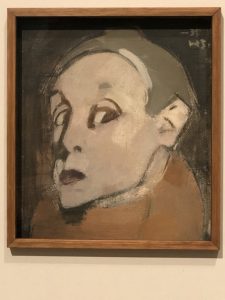

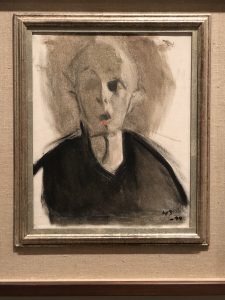

Nevertheless, the Schjerfbeck exhibition at the Royal Academy provides us with the excitement that comes from once again challenging and expanding the canon. Let’s hope we see more museums willing to take these risks.

Nevertheless, the Schjerfbeck exhibition at the Royal Academy provides us with the excitement that comes from once again challenging and expanding the canon. Let’s hope we see more museums willing to take these risks.

,

, interesting. And one wonders whether either artist ever encountered the wonderfully concise MirrAnd oneored Room (1966) by Lucas Samaras (

interesting. And one wonders whether either artist ever encountered the wonderfully concise MirrAnd oneored Room (1966) by Lucas Samaras (

breaking Lumia works, which he began as early as 1919, and which were the subject of a compelling recent (2017)

breaking Lumia works, which he began as early as 1919, and which were the subject of a compelling recent (2017)

,

, DeStaebler,

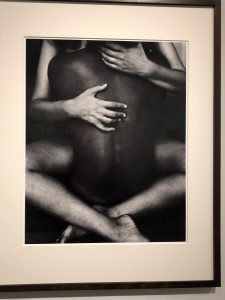

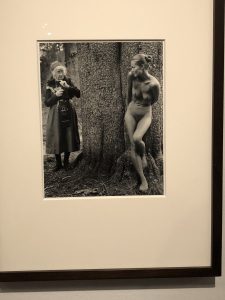

DeStaebler, or a slew of these other artists at SFMoA (which has them in the collection)? The strength and range of the Saxe gifts is super, especially since it does so much to expand our understanding of an important aspect of California art. There’s also a powerful Judy Dater exhibition,

or a slew of these other artists at SFMoA (which has them in the collection)? The strength and range of the Saxe gifts is super, especially since it does so much to expand our understanding of an important aspect of California art. There’s also a powerful Judy Dater exhibition,

The deYoung shows real respect for California artists (which is more than you can say for SFMoMA). It may not be a truly encyclopedic museum, but it is energetic and exciting in its range. (Again I didn’t see the special exhibition, “Cult of the Machine”, because I wasn’t about to pay $28.)

The deYoung shows real respect for California artists (which is more than you can say for SFMoMA). It may not be a truly encyclopedic museum, but it is energetic and exciting in its range. (Again I didn’t see the special exhibition, “Cult of the Machine”, because I wasn’t about to pay $28.)