Recent Japan travels reminded me of how museum rules and regulations are supposedly important for the protection of what’s on view, while also too often being arbitrary. But I could as well have thought of this elsewhere, since I recall being asked not to use a pen in some museums (SFMoMA comes to mind) – and even being provided with a pencil to use (the graphite point, with which I might puncture a canvas, presumably being less destructive to works of art than the ink of my ball point or fountain pen). Presumably my bona fides as a responsible visitor are not validated by something as insignificant as my ICOM and/or AICA card. That’s OK. I’m not a big fan of rank. The “no flash” camera rule seems reasonable, since it might annoy fellow visitors; but the argument museums often give is the destructive power of that flash of light on works of art (especially those on paper). I hope some conservator has done a thorough study of just how much damage is done by the occasional flash vs. the damage done by exposing the art to viewers at all. I can’t recall the last time I saw an actual flash bulb pop anywhere but in retro movies.

Demystifying museums has always been among my life goals, although I probably can’t point to very many successes in that endeavor, even after half a century of museum work. It’s what you’ve come to see that might be – hopefully will be – magical, not the institution that’s there to make it accessible to you. Trying to capture that magic and take it home with you seems like a reasonable urge. We know we can’t really “capture” the magic, but one can’t always restrain the impulse. In this age of smartphones, it’s no longer only the Japanese tourists that are camera crazy. “Kodak moments” have proliferated along with the demise of Kodak. In places with ‘unforgettable’ views one might even have to queue for the right spot to click the smartphone. The Louvre has tried to solve this problem, while creating new ones (maybe the newest definition of ‘distance learning’?) in its recent reinstallation of the Mona Lisa.

I was trying to figure out what lies behind the many museum photography restrictions in Japanese tourist venues (museums and other sights). It can’t be simply to protect the [often] non-existent rights to images, or some false sense of security. In a few places highly visited and space-restricted venues the goal is probably to keep traffic moving. So I applaud those rules, just as I sometimes happily flaunt them.

For some reason, while I was in Japan I was led to thoughts of my favorite rogue museum photo scoundrel. His name was Samson Feldman and he lived with his sister, Sadie, at 3900 North Charles St., a banal 1950’s(?) red-brick apartment house in Baltimore, near my own home, when I served as director of The Baltimore Museum of Art in the 1970’s. Samson was a delightful old man (at the time surely at least a decade younger than I am now), who traveled everywhere to see art museums. When I would take a trip to France or Italy, he told me proudly that he couldn’t go to see museums in Europe because he hadn’t yet seen all the ones in the USA! He was also an artisan of sorts (I still have a few silver objects he gave me), and a collector of antiques. I was under the impression that he had been an antiques dealer before I met him, but I can’t find any references to that. He was among the BMA’s most loyal followers, coming to every exhibition, and taking photos at openings, events, and of the exhibitions themselves. He often would send me a card with a photo of me (and my wife and/or children) taken at a museum event. He lived with his spinster sister, Sadie, in a well-appointed, but unpretentious, apartment filled with American antiques and lots of art books. Samson died in 1983, so I was delighted to see that Sadie, who died in 2005, gave the BMA their scrapbooks (now part of the museum’s Archives) of the photographs Samson took. Sadly, however, there’s no mention of my favorite of Samson’s many photographs: at the Barnes Foundation, when it was under the watchful and policing eye of Violette de Mazia (1899-1988) – at that time still the commander-in-chief (and watchdog), who had worked for the quirky Dr. Albert C. Barnes and tried to carry on his mission following his untimely death in an automobile accident in 1951. (Despite speculation about whether de Mazia’s relationship with Dr. Barnes was more than colleagial, no conclusive evidence on that subject seems to have come to light.)

But I digress (which is the point of these meanderings). Those of us who had visited the Barnes when it was first opened to the public, following a lawsuit (only the early phase for a slew of Barnes lawsuits) – I think it may have been 1963 or 1964 – remembered the strict regulations about carrying anything around. I think pads and pencils were permitted, but no handbags and certainly no cameras. The regulations surely weren’t about flash bulbs and conservation, and since the visitor numbers were purposefully sparse (in those days a reservation had sort of trophy status), the Barnes zealously protected the “rights” of their images, as did most museums at that time. Unlike the Barnes, which laid no claims to being public or hospitable to anyone but its students, most museums claimed that their art belonged to ‘everyone’ – except that the image apparently only belonged to the museum. Technology has changed much of that by now. But in those days, I would never have dared to attempt surreptitiously taking photos of works in the Barnes collection. (I know nothing about the current photography policy at the “new and improved” Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia’s central city.)

Enter Samson Feldman. He came to my BMA office one day (probably 1972-73) and proudly showed me the entire Barnes collection in photographs which he had managed to take on a recent visit. And he then took out his Minox camera and explained how easy it was to photograph the Barnes collection. I knew what a Minox was because my father had one (although I don’t think he ever put it to such good use); it was a sort of early version of the “whoever dies with the most toys wins” syndrome. I asked Samson how he had evaded Miss de Mazia, and he said, with a gleam in his eye, that was no problem at all, given his Minox expertise. If those photographs are among the ones in the BMA Archives, they may well have some archival value; but the online finding aids don’t list them.

Having just spent several weeks in places that don’t permit visitors to take photographs, I fondly remembered Samson Feldman and wondered how he would have used his iPhone; despite his persona of a dour conservatively-dressed elderly gentleman, he had a great sense of humor and surely would have carried the latest iPhone model. If there’s an ethical dilemma, it comes down to which rules you obey and which ones you flaunt, and how you rationalize your actions. In Japan travels that was simple for me. A religious site (temple or shrine) that’s being visited by at least some people who care about that religion, meant that I wouldn’t take photographs, out of respect for the place and the people (and the rules). But if it was just a visiting site (or clearly de-sanctified religious place), then I felt free to figure out ways of taking photographs, in spite of the rules. Note: I’m only referring to use of my iPhone X, not to a real camera – that would be a lot more visible, difficult and therefore perhaps riskier.

There may not be rules, but there’s a routine. When there’s a ‘no photo’ sign (vs. the ‘no flash’ sign – don’t get confused) you start by checking out the guard or watchman situation. Is the person in a fixed location or does he/she move around? Does the guard appear bored, wishing he had a better job, or is she super attentive, believing that museum guard is like being part of the POTUS Secret Service detail? Can you determine a pattern in his movements – doing regular rounds or erratically moving around? If the former, the guard may be away long enough for you to get that great shot. Are there other people around to shield you or are you out there on your own? A companion is useful for standing between you and your camera (iPhone) and the guard. If you need to hold your iPhone in an awkward position so the guard won’t see you, will you still get a photo worth taking? Finally, how many times can you handle the humiliation of being told that no photos are permitted – especially by the same guard? Japan turned out to be especially onerous, since there were so many places with no-photo rules. On the other hand, that also turned into a challenge. Who doesn’t like to surmount a challenge?

Previous to Japan, my most recent experience with trying to outwit the no-photo system was in April 2018 at the Prado, where I fell in love with Bosch’s Adoration of the Kings triptych (1485-1500) and desperately wanted my own image of it.

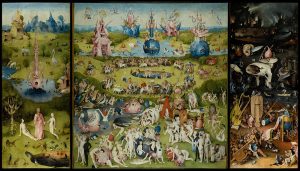

But getting a clear photo straight on, while being sneaky, is no mean feat. In that gallery most of the attention was on the more celebrated Bosch Garden of Earthly Delights (1490-1510), which attracts huge crowds and therefore requires more guard attention.

(above is not my photo!)

As luck would have it, the guard in that gallery did make a fairly regular and trackable circuit, which I could figure out after a while – except when that routine was interrupted by excessive jostling around the Garden painting. I did eventually get my photos, but there was never enough time for the details which I so badly wanted – more clarity on the extraordinary crowns of the Kings, and more of the genre scenes, such as Joseph doing his (and the Virgin’s?) laundry, on the left wing.

More time might have yielded those, but there was so much else to see in the Prado. And in the Velázquez galleries I admit to having understood why the Prado’s no-photos rule is so important. The number of people wanting selfies with Las Meninas (1656) would make seeing that glorious painting impossible, and the crowds are significant even without selfies.

(above is not my photo!)

On the other hand, once you get into the joy of surreptitiously taking museum photos, it’s difficult to stop, especially at a museum as wonderful and inadequately vigilant as the Prado. So among my several other transgressions (triumphs?), the joy of seeing both of Goya’s Majas (1797-1805) side-by-side was too great a photo op to miss, despite the fuzzy results.

It ‘s still unclear to me why Japanese museums would have the no-photo-rule, since most of them were not so full of visitors that picture-taking would be problematic or traffic-stopping.

On the other hand, the many temple gardens we visited seemed to demand silence and contemplation while also insistently beautiful, wanting to be photographed. The challenge (unmet!) was to figure out how one could capture the abstract subtleties of light and shadow while also retaining the meditative silence. Most of the temple gardens had assertive no-photo signs, but that didn’t stop me (if no one was sitting in meditation and no guards were in view). You can’t really capture that mysterious feeling of contemplating minimal rows of grey stones. Ultimately the stone gardens’ inscrutability triumphed over my scofflaw instincts.

More closely restricted from photography (because well guarded!), much to my grudging satisfaction, is the so-called Teshima Art Museum, a confection by Ryue Nishizawa, one of the co-founders of the SAANA architectural group, with the collaboration of Rei Naito. I find a special perverse satisfaction in not being able to describe this non-museum. It’s part earthwork, and mostly experiential, demanding close quiet attention in the way that a Bill Viola video might. And it shares in the meditative qualities of Japanese gardens, ever re-revealing itself. Like a Viola piece, the Teshima work is minutely calibrated and dependent on unseen technology, while somehow persuading you that you’re engaged in the minute observation of natural forces. So exterior photos (which are permitted) tell you nothing about the experience. The “museum’s” isolation — it’s a long hike (or beautiful bicycle ride!) from where the ferry drops you off — is part of the memorable experience, as is one’s inability to actually find the words to describe what it’s all about. Even the photos of the exterior (below) reveal nothing about what’s inside.

The other, sort of nearby, mecca for contemporary art enthusiasts is the island of Naoshima, also on the Seto Inland Sea, at the southern edge of Honshu, Japan’s largest island. Once again the mysteries of no-photo rules proved both a puzzlement and a challenge. The outdoor pieces in the mélange of site-specific and/or beautifully placed works on Naoshima were all available to be photographed, and three George Rickey sculptures must count as among the artist’s best-sited works, begging for photo ops.

The Benesse Art Site, which is the owner/collector/ commissioner of a fairly vast array of wonders on Naoshima Island, remains mysterious as to its funding, organizational, and curatorial structure. But that seems inconsequential in relation to the many fascinating visual revelations. Architect Tadeo Ando is presumably a co-conspirator here, not only with the architecture but probably with many of the siting issues as well. Visiting Naoshima one can better understand why clients such as Williamstown’s Clark Art Institute would have found Ando such an appealing choice for a major architectural makeover. But my better sense of Ando’s aesthetic, seeing his work at Naoshima, did nothing to win me over to The Clark’s clumsy plan. At Naoshima there’s a[n occasionally frustrating] sense of discovery entirely missing in Ando’s Berkshire venture.

Despite a few appealing works that suggest the arbitrariness so often associated with “plop art” — e.g., Yayoi Kusama‘s pumpkin out on a pier (more of a branding exercise than an interesting sculpture), and both

Karel Appel‘s and Niki de Saint Phalle‘s “fun” lawn sculptures — those

felt arbitrary in comparison with so much that is (and feels) purpose-built at Naoshima.

In the museum settings, it was again a cat-and-mouse game of trying to elude the policing that kept one from snapping photos. The Benesse House Museum seemed needlessly strict about photos, but I still got to sneak a few, including some fine pieces by Richard Long.

My favorite here was the wonderful Jennifer Bartlett 1985 boat painting. But an especially watchful guard kept me from taking a straight-on photo.

To see the boats “echoed” on a beach nearby (photos permitted: it’s outside) gave a special eery resonance to Bartlett’s work.

A wall of small Kuniyoshi works, also secretly photographed, doesn’t provide much of a souvenir, since they would each have had to be photographed separately — not an option, given where the guard

was standing. It was also a bit puzzling as to why this artist was included in an array of primarily contemporary art works. Still, there’s something engaging about seeing a selection of art that’s not an “overview” of anything, but rather represents personal choices — even if we don’t get to know the identity of those involved in the choosing.

The Lee Ufan Museum may have been the most challenging of the Naoshima no-photo sites. Another collaborative Ando effort, this museum does well demonstrating the eponymous artist’s range, even if the outdoor works (photos permitted) may be overly reliant on their setting, suggesting earlier artists (e.g., Robert Grosvenor) and what we might think of as the Storm King (and other sculpture gardens/parks) aesthetic.

I admit that trying to elude the guards to take photos of Ufan’s work inside the museum made the art feel more engaging than it might otherwise have felt. A spare Japanese aesthetic overlay doesn’t completely mask a likely debt to many other artists.

I’m not sure I would have been as engaged by Lee Ufan if it hadn’t been for my game of trying to nab some photos before the roving guard reappeared.

If beating museum regulations is its own sweet private game, it’s nevertheless more relaxing to be at ease in a museum that’s too small (or too poor) to maintain a security staff that polices photography. So it was a joy to take so many illicit photographs of the ceramics at the Kurashiki Museum of Folk Crafts — surely one of the best arrays of mingei ceramics we saw in Japan.

Given the array of images now available on the internet, it may seem redundant to play at capturing less distinct images on an iPhone, simply because it’s fun to play a game of museum cat-and-mouse. But there are enough instances of finding a wonderful image that “demands” to be captured, that one has never seen before and may never again encounter. Such a memorable work is Léonard Tsuguharu Foujita‘s Avant le Bal (1925)

now at the Ohara Museum of Art in Kurashiki (a charming city whose one canal earns it the strange misnomer ‘the Venice of Japan’).

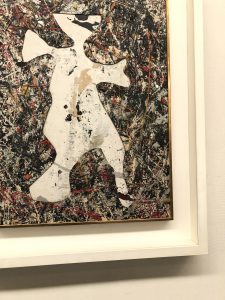

I haven’t been able to find it on the internet, yet it may be the artist’s chef d’oeuvre, emerging from the both Cézanne and Puvis de Chavannes, along with an obvious relationship to Picasso’s Demoiselle d’Avignon and his Saltimbanques. A number of other interesting works at the Ohara Museum would have merited better photographs — for example the 1948-50 Jackson Pollock Cut-out,

for which I was only able to manage a bad photo, as well as a Rothko

painting and some other intriguing works. But although the galleries were not especially crowded, the no-photo rule was being quite strictly enforced.

On the other hand, the Ohara was worth visiting for the Hamada ceramics alone. And especially stunning array of this incredibly influential master and teacher — and, visa Bernard Leach, source of so much of the rich 20th century British ceramics tradition. And they weren’t as careful about guarding the ceramics from photography, despite the official prohibition.

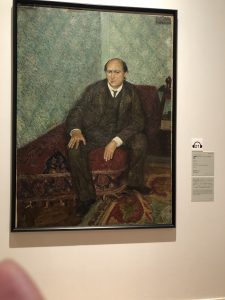

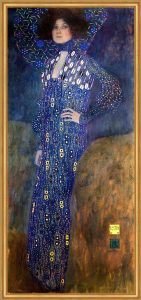

The ever-changing illogical rules about photography were especially amusing at the National Museum of Art in Osaka. An extensive and fascinating special exhibition, Vienna on the Path to Modernism, celebrating the 150th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Japan and Austria, consisting primarily (or exclusively?) of loans from the Wien Museum. Here the zealously overseen no-photo rule deterred me a bit, although I managed to sneak in a few snaps.

Most astonishing was the “OK to photograph” sign by the splendid Klimt portrait, which seemed like a generous gesture until one realized that the

space and lighting was not likely to yield much of a photo. This Portrait of Emilie Flöge (1902–03) was only one highlight in an exhibition with some

wonderful works, but the internet yields better images (albeit not on the Wien Museum’s website)!

(above not my photo)

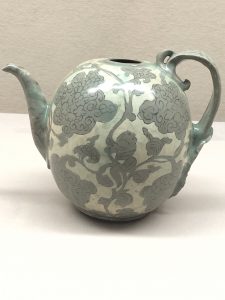

Finally, in the realm of thoughtful and visitor-friendly museums, nothing in Japan beats the Osaka Museum of Oriental Ceramics! The signage is clear and inviting, which is great for anyone who revels in Asian ceramics.

So it was an endless feast, especially the superb examples of Korean ceramics, a special love of mine. And I was set to wondering once again

about the shortsighted and miserly approach of so many museums to visitor photography. There are surely venues in which crowd control, security or similar concerns are valid. But possessiveness about visual images that constitute much of the museum’s raison d’être are generally silly, and will continue to encourage the joys of being a scofflaw.

Here’s to digressions!

At just about the first time you went to the Barnes in the 60s, I too paid my first visit. One detail about their then rules still boggles my mind.

If the entry guard thought a woman’s heels were too spiky, he would give the offender corks to put on to the point of their heels so that they wouldn’t ruin the floor.

Happy Hanukkah!