It was late spring 1977 when a young man asked to see me in my office at the Baltimore Museum of Art, of which I was director. In line with my policy of not screening visitors, I invited the fellow in. He introduced himself as John Kinsley, and said he was a poet. He was slightly scruffy, albeit very polite, and carried a small insulated cooler – the kind one takes along on picnics. He then asked whether he might use my conference table, and when I assented, he proceeded to open his cooler, taking out some wooden blocks, which he arranged on the table. On top of the blocks he placed ice cubes, the entire assemblage spelling out M-E-L-T. John then told me that he wanted to recreate this word (poem) in large form on the museum’s front steps in mid-summer. When I asked how this could be managed, he said he had already arranged for an ice company in Pennsylvania to deliver blocks of ice, and that this could all be done at no cost to the museum; he would use his own money. I was concerned about whether the museum steps could bear the weight of so much ice (15 tons!), but since I found the idea intriguing, I agreed to have engineers check whether this was safe and feasible. They assured me that it was.

Planned for the weekend when July and August met, the event was postponed for a week because of intense July heat and floods in Johnstown, Pa., from where the ice was to be delivered. So the event happened the following week-end, early August, with what would pass for considerable fanfare in Baltimore. According to local art critic, Barbara Gold’s, report in the Baltimore Sun (my memory isn’t sufficiently detailed), there were seven tiers of 120 ice blocks, each block weighing 300 pounds, held together by lucite pegs. The poem was 60 feet long and titled Revenge on the Winter of ’77. Many people came to watch, and there were a large group of stalwarts who spent the sweltering night watching the ice poem turn into water. I was one of them.

Having grown up in Buffalo and having missed (but read about) the infamous Winter of ’77, perhaps I had a special affinity to young (age 29) John Kinsley’s poem. But like most ‘sensational’ events, this one passed with minimal outside notice, other than the double page spread of an aerial view of “MELT” in a national magazine whose name I’ve forgotten.

Memory of this long-ago non-event came rushing back to me when I visited the exhibition, Olafur Eliasson: In real life, at London’s Tate Modern. A much-celebrated show about a much-celebrated artist, the exhibition warranted a long and thoughtful piece by Ingrid D. Rowland in The New York Review (9/26/19), where she wrote:

“To focus public attention on the present unfolding tragedy, Eliasson has created Ice Watch, blocks of eerily blue Greenland ice set out to melt [in Copenhagen, then Paris, then London]. The installation brings a miniature version of Greenland’s catastrophic melt close enough to touch…”

I decided not to worry about the amount of energy expended on transporting actual Greenland ice around Europe, although I did remember that John Kinsley was only moving ice from Pennsylvania to Baltimore. His poem also predated current concerns about global warming, which may have impacted the notorious Winter of ’77, even if few people recognized it at the time. Nevertheless, the Eliasson exhibition is a reminder that there’s not a lot new under the sun – other than his sun. The artist’s 2003 work, The weather project, still resonates with me as the single most impressive of the many

Turbine Hall installations at Tate Modern. That challenging cavernous space has never again been so wholly engaged, despite valiant attempts by an array of celebrity artists.

The Eliasson exhibition may be most exciting for visitors with short memories or minimal knowledge of other artists whose work it recalls. That excludes the once-young Mr. Kinsley, who considered himself a poet (not an artist), and whose whereabouts I have been unable to determine, despite my best googling efforts. Many of the works in the exhibition play with our ideas about sensory issues. However, of the five senses – sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch – only the first two work in a museum gallery context. Touch is surely verboten! For smell and taste you would need to visit one of the Tate’s several eating venues.

At a moment when people are queuing up for hours to experience Yayoi Kusama’s mirrored rooms ,

,

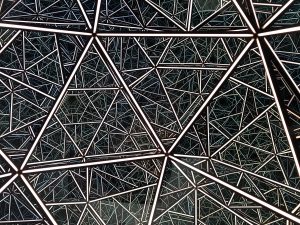

Eliasson’s walk-through Kaleidoscope (2001) – for which the Tate is stuck apologizing because it’s not handicapped accessible – actually isn’t very interesting. And one wonders whether either artist ever encountered the wonderfully concise MirrAnd oneored Room (1966) by Lucas Samaras (Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo).

interesting. And one wonders whether either artist ever encountered the wonderfully concise MirrAnd oneored Room (1966) by Lucas Samaras (Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo).

And walking down New Bond Street the other day, I passed the Opera Gallery, in whose window I saw yet another ‘with it” artist (Anthony James) playing with mirrors in a manner that was quite effective.

Eliasson’s large disk with projected moving forms is a version of Thomas Wilfred’s many ground-

breaking Lumia works, which he began as early as 1919, and which were the subject of a compelling recent (2017) exhibition at the Yale University Art Gallery.

breaking Lumia works, which he began as early as 1919, and which were the subject of a compelling recent (2017) exhibition at the Yale University Art Gallery.

When museums celebrate (or should we say promote?) artists with major of-the-moment reputations, it would be helpful to give viewers some context. Eliasson’s experimental workshop and engagement with young people, as well as his political activism, can be applauded without the pretense of suggesting that his ideas have no precedents. Happily, a concurrent Tate Modern retrospective exhibition of the Greek artist, Takis (real name: Panayoitis Vassilakis, 1925-2019) reminds viewers (although there seem to be fewer of them than in the Eliasson exhibition) that many artists have experimented with technology and perception. Although a few early works demonstrate his aesthetic origins in Cycladic art, Takis experimented endlessly with perceptual issues involving magnetism, sound, and space.

And Takis even shares with Eliasson the relatively rare commitment (or artists) to political activism.

I remember working on an exhibition, Directions in Kinetic Sculpture, organized by Peter Selz at the University Art Museum (now Berkeley Art Museum/Pacific Film Archive) in 1966, when the gentle and affable Takis arrived to assist with the installation of his sculptures. The show also included work by Fletcher Benton, Davide Boriani, Robert Breer, Pol Bury, Gianni Colombo, Gerhard von Graevenitz, Hans Haacke, Harry Kramer, Len Lye, Heinz Mack, Charles Mattox, George Rickey, Takis, Jean Tinguely, Yvaral. Vasarely) I had recently arrived from helping on the exhibition, 2 Kinetic Sculptors: Nicolas Schöffer and Jean Tinguely, organized by Sam Hunter at New York’s Jewish Museum. What was then generally called “kinetic art” has a significant exhibition history . I guess that one should feel satisfied to see that, now and again, museums remind us, even if unwittingly, about the nature of art and discovery. But they could do better telling visitors about the shoulders of nearly-forgotten artists, if not giants, on which so many of today’s artists stand.

So, what became of John Kinsley??

As a former staff member of the Albright-Knox I do remember the ‘Blizzard of 77′ but more to the point have often wondered whether Yayoi Kusama was aware of Samaras’ Mirrored Room at the Albright-Knox. The first Infinity Room appeared almost simultaneously with the Samaras although there is evidence that Samaras had originated the idea some years before. Of course this was a time when perceptual art (Op and Kinetic) were gaining momentum and sometimes ideas are just “in the air.” The larger point, though, is undoubtedly true–art builds upon its own past and most artists (the best ones) understand and use precursors and precedents to fuel their own creative impulse and impetus (something the Albright-Knox permanent collection uniquely provided evidence of).