During an early October (2018) visit to Auschwitz (my fourth or fifth time; my first was in the summer of 1963) with an extraordinary group of friends under the auspices of FASPE, I was once again reminded that one picture is definitely not worth a thousand words. A small country cottage stands across from the railroad tracks near the entrance to Auschwitz I, and in the yard is a jungle gym for the kids of the presumably Polish family who presumably live there. I could not help but wonder whether they had any knowledge or understanding of those tracks.

How could I not be reminded of the jungle gym we have set up for our grandchildren at our Royalston (Massachusetts) farm, although we’re a tad more rural and the rail tracks in the south village aren’t as regularly active as the ones at Auschwitz once were.

But the experience took me back to the late 1970’s, when I was persuaded to organize an exhibition and compile a catalogue of art created in concentration camps– I believe the first such exhibition in the USA — from the collections of the museum at Kibbutz Lohamei Ha’Geta’ot (Ghetto Fighters’ Kibbutz) in Israel. The kibbutz was founded in 1949 by the last survivors of the Warsaw Ghetto Revolt. Miriam Novitch, an indefatigable member of that group, had assembled the collection from a variety of sources (survivors, their families, and probably some unsavory places as well). I had been introduced to her by art patron and collector (primarily of contemporary British art), Melvin Merians (1929-2009), who presciently persuaded me that this material needed a more public viewing. The exhibition was shown at the Baltimore Museum of Art, of which I was then director, and subsequently at New York’s Jewish Museum, Harvard University, and several other venues. This was almost a decade before Claude Lanzmann’s 1985 film, Shoah, transformed or reanimated interest in the Holocaust.

Even then, I had an uneasy sense about using art to generate interest in the Holocaust. I had always known that my sister, Margit, born in Berlin in 1928, had been deported — presumably to Auschwitz — and we assumed had been murdered there.

But it was only in 1983, after the publication of Serge and Beate Klarsfeld‘s monumental book, Memorial to the Jews Deported from France, 1942-1944, that my family learned the details: the precise date of her deportation from Drancy (November 6, 1942), the train number (convoy 42), and the names of the other victims on that train.

In those days, before the fashion of ubiquitous Holocaust museums, treating art as an potential entrée into a horrible subject seemed appropriate. Indeed, the first book that presented so-called Holocaust art was I Never Saw Another Butterfly: Children’s Drawings and Poems from the Terezin Concentration Camp, 1942-1944, edited by Hana Volavkova (1904-1985). She was the only curator of the Central Jewish Museum — the massive Prague-based Nazi project to collect all Jewish artifacts — to survive the war. Originally published in 1959, this extraordinary book was a bestseller in its time, and remains in print today.

Surely images can give us insights. After all, the “utilization” of images to educate while also manipulating a range of sentiments lies at the heart of much religious art. But images can also mislead us. Here’s my iPhone photo of the notorious sign at the entrance to Auschwitz, decorated by the first touches of fall foliage.

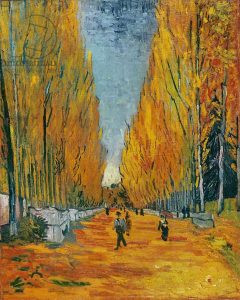

Now check out the elegant allée of poplar trees just a few steps away.

How could I not be reminded of Van Gogh’s painting, L’Allee des Alyscamps, Arles (1888)?

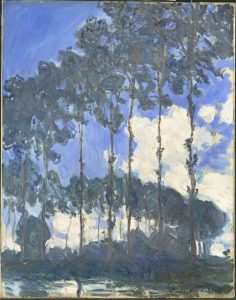

And also any number of other poplar images that were a staple of French Impressionist painting, such as Claude Monet’s 1891 Poplars on the Epte.

I also thought about the poplars at my farm, since I watch them intently all summer. They have a special elegance about them which makes me understand why the French painters found them so alluring. Indeed, we sit and watch the poplars to check on the wind, since their leaves are so light and delicate that they flutter in the slightest breeze.

But this has nothing to do with the Holocaust, and although I’ll surely remember Auschwitz next summer when I sit and contemplate my trees, I’m not sure I want to see them as a permanent mnemonic device to conjure up thoughts of the Holocaust.

Images can be confusing in so many ways. In the days when I used to lecture about Holocaust art, I often began with the series of paintings by the American artist, George Bellows (1882-1925). He had read about the Battle of Dinant, one of the earliest conflicts of World War I, when German troops invaded that Belgian town in August 1914. In 1918 Bellows produced a series of canvases, which he called Massacre at Dinant, that includes images easily read as Holocaust images, such as The Return of the Useless depicting a railroad box car and violence.

In this series Bellows also painted The Germans Arrive, and

The Barricade.

Bellows was probably inspired by a magazine article published in February 1918 by Brand Whitlock, titled “Belgium: The Crowning Crime” or by an earlier (May 13, 1915) New York Times article. The war was over by the time these works were shown, so they have to be viewed in the context of history painting, which is an altogether different subject. Nevertheless, a superficial reading of the works could lead us elsewhere — for example to the idea of pre-Holocaust imagery.

Surely Bellows knew he was following in the footsteps of Francisco Goya (1746-1828), whose majestic Third of May, 1808 was painted in 1814 to commemorate Spanish resistance to the Napoleonic occupation of Spain.

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) responded more rapidly to an important historical event. Hearing about Nazi planes, in support of Franco’s forces, bombing the Basque town of Guernica on April 26, 1937, Picasso started to work on Guernica by May 1st, creating what is surely the 20th century’s most significant political painting.

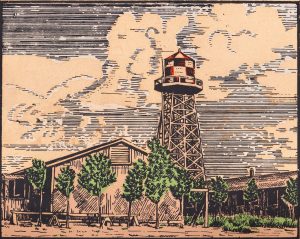

Nevertheless I wonder whether there isn’t an inherent danger when we rely too heavily on “art” for our understanding of tragic events. Sometimes we may misunderstand. This woodcut of a watchtower from the page from the Camp Amache Christmas Calendar might be misleading if we’re told that it’s from a relocation camp. Officially the Granada War Relocation Center, opened in 1942, Camp Granache was one of the venues for the “relocation” of Japanese-Americans during World War II.

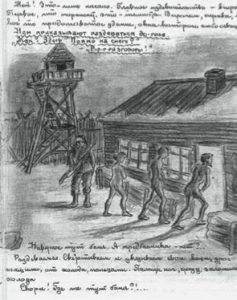

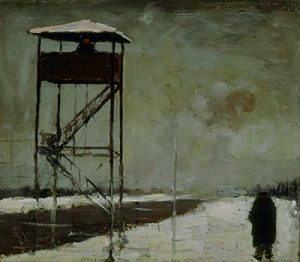

But one tower isn’t necessarily just like another, as we can see in this drawing from Thomas Sgovio’s 1972 drawing of the harsh conditions in the Soviet Gulag.

Nor is it the same as this image by Josef Nassy (1904-1976), a Black expatriate of Jewish descent, who was one of 2,000 internees with American passports held prisoner during World War II.

Towers can be as misleading as swing sets. Here’s a Japanese-American child’s drawing from an internment (sorry, relocation) camp, and without any context it tells us little about the circumstances of its making.

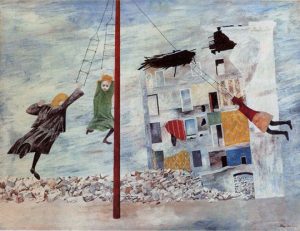

In his joyous painting, Liberation (1945), American artist Ben Shahn (1898-1969) used kids swinging amid destruction to celebrate the end of World War II

Still that’s not quite the same as our grandkids having a good old time at our farm.

The most serious exploration of Holocaust-related art — treating it seriously as both art and visual testimony — was probably undertaken by Glenn Sujo in a groundbreaking 2001 exhibition. “Legacies of Silence” was shown at London’s Imperial War Museum, and in the accompanying catalogue/book, Legacies of Silence: The Visual Arts and Holocaust Memory, Sujo adds much-needed art historical context to the work done by so many serious artists who deserve to be viewed within the broad scope of twentieth century art. Israeli scholar, Ziva Amishai-Meisels, has also written meaningfully about this field.

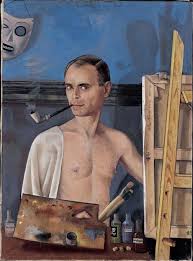

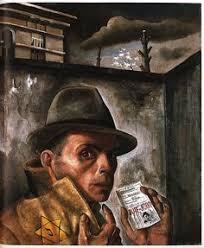

That’s not unimportant, since a number of these incarcerated and murdered artists had serious careers. Among the best known was Felix Nussbaum (1904-44), who was born in Osnabrück and trained in Berlin. His 1943 self-portrait as a painter, executed while he was in hiding in Brussels, contrasts with another one of the same year, in which he shows himself with a “Jewish passport.”

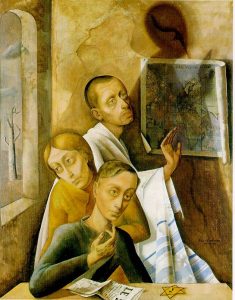

In one of his last pictures, Threesome (1944), he clearly identifies himself as a Jew. Not long after completing this painting, Nussbaum was murdered at Auschwitz.

Nussbaum is now celebrated in the Felix Nussbaum Museum, part of Osnabrück’s Cultural History Museum, which was opened in 1998 in a building designed by architect Daniel Libeskind.

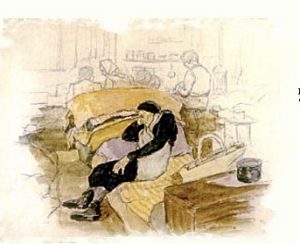

My own “favorite” among these artists is Prague-born Malvina Schalkova (Schalek) (1882-1945), who managed to create over 100 drawings and watercolors depicting scenes of daily life in Teresienstadt (Terezin) showing the inmates’ gentle humanity as they cope with their tragic situation.

Trained in Munich, Schalek had a significant career as a painter in Vienna prior to her deportation to Terezin. She was later transported to Auschwitz, where she was murdered. Her tender watercolor of the tired old lady in a Terezin barracks moves us because of its universal sense of compassion, not just because we know where it was created.

These ruminations stem from my encounter with the sense of quotidian humanity expressed by a jungle gym at the entrance to Auschwitz. I don’t know anything about the family living in the small cottage by the railroad tracks. I have to assume they are folks who found a reasonably-priced plot of land on which to build their house and raise their kids. I wish them well.

I’m posting this on November 7, 2018. That’s a sort of frightening day — arriving between an American election in which too many voters ratified a President spewing xenophobia and hate, and the 80th anniversary of Kristallnacht, which (we need to remember) didn’t arrive until five and a half years after the Nazis seized power.