“Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me.” But what if I didn’t get fooled at all, even though you tried? Damn: the cliché doesn’t include that.

Those are my Damien Hirst-related thoughts after visiting “Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable” at the Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana in Venice, the biggest hanger-on to this year’s Venice Biennale.

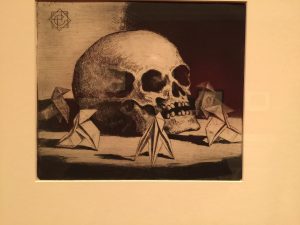

OK, we already knew that Damien Hirst was all about money. Remember his 2007 diamond-encrusted skull, with 8601 flawless pavé-set diamonds?

Remember how relieved we were to know that all the diamonds were ethically sourced for the work? Were you tempted to buy one of the limited edition (1000) silkscreen prints with glaze and diamond dust on the skull, because you couldn’t afford the real thing?

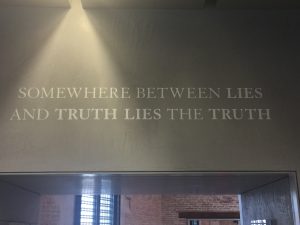

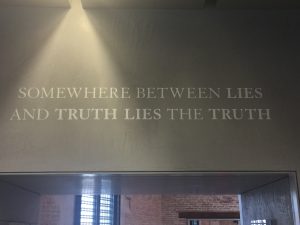

Well, diamonds may be forever, but they just start as some crappy coal bits from the ground. Which isn’t nearly as interesting as finding a nature-encrusted long-lost sunken treasure in the sea. The brilliance of this Damien Hirst conception is somewhere in the realm of classic one- liner jokes: “why did the chicken cross the road” and its relatives, e.g., “why do firemen wear red suspenders?” and so on. At the Dogana we even are treated to a pithy epigram, presumably from the artist’s own intellect, slightly less deep than the waters from which these treasures were “rescued”: “Somewhere between lies and truth lies the truth”

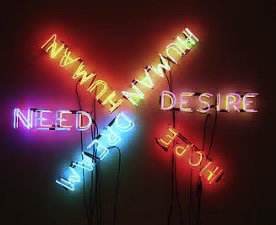

Even Bruce Nauman does better than that!

It’s impossible not to concede that Hirst’s double-whammy exhibition (two major venues) is spectacular and brilliantly conceived. (Perhaps the guy who originally thought of asking why a chicken crossed a road was no dope, either.) But since the joke is so lame, one is mostly overwhelmed by the spectacle and the presumed cost of arranging it all. Sort of Las Vegas, but without the fun. Hirst has made a lot of money in the inflated art market. After all, why should the dealers be the only ones to get rich? And the cost of creating his fantasy – surely many millions – has not been revealed (so far). Nor has the hefty investment of his patron, François Pinault, owner of Christie’s and a lot more, to make this greatest show on earth (well, in Venice, anyway) possible. Supposedly the works have been offered to collectors at prices start at around $500,000 apiece and rising to upward of $5 million. But they aren’t on the market yet (or maybe they are), so who knows.

The artifice could be considered “brilliant” if it weren’t such an obvious and shabby hoax. I have a long-time hoax fetish, so after an artist friend of mine told me he was confused when he first visited the show, thinking it might really be an underwater discovery, I was excited at the prospect that someone had carried it off. But alas, it’s lame. You never get sucked into the story, despite a 72-page booklet (free with entry ticket!) and

the staggering amount of technology and money and thought and analysis that has gone into making it an exciting hoax. It’s not even a fun hoax. A few years ago my college classmate, Arthur’s, wife sent us all an e-mail telling us that Arthur had died, and we responded with condolences and reminiscences. So we were pretty pissed off when Arthur told us he was still around (sadly, in the meantime his wife has died). But we got the idea that we all had our collective leg pulled and that the hoax had worked.

The fantasy that Damien Hirst creates is about the discovery of a sunken ship, the Apistos, off the coast of East Africa. The owner, a freed slave, who lived between the mid-first and early second centuries C.E., had amassed one hundred fabled treasures – “commissions, copies, fakes, purchases, and plunder” – and after the vessel foundered, all of this “lay submerged in the Indian Ocean for some two thousand years before the site was discovered in 2008.” A model of the ship has been created, along with a sophisticated video assist — touch-screen and all — that helps you navigate (pun intended) the ship’s interior to see where the treasures are believed to have been before the Apistos sank.

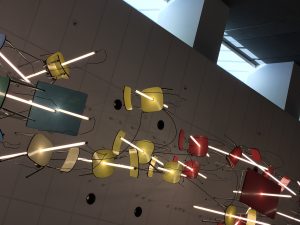

The exhibition displays the discovered objects, as well as spectacular films — the kind we see in science museums — documenting the raising of these treasures from the ocean’s floor. Watching recovery sea divers at work, and then seeing those very objects in the gallery should be thrilling. But it isn’t. How not to think about what it must have cost to create these objects, hire the ships and divers, pay for underwater film crews, put the artifacts into the ocean (or water somewhere) just for filming and then get them back up for display. It’s staggering! An amazing theatrical feat! Something on the order of Lon Chaney in “Hunchback of Notre Dame” or Arnold Schwartzenegger in “Terminator.” And while it may be extensively photoshopped, all the photo and film imagery looks really real. (But remember, if you go to Atlantis in the Bahamas you might even find yourself in the water and have more fun.) Then there’s the cost of the studio assistants (many!) to mold and carve and assemble all this stuff, some of which is immense, rising several stories inside (and outside) the fabulous exhibition spaces.

This must have required a range of quite specialized skills — involving more than what’s probably in the toolkits of the the many wannabe artists who are often studio assistants. Simply supervising the entire confection has to have been incredibly labor intensive – and costly. This could be a Harvard Business School management case study.

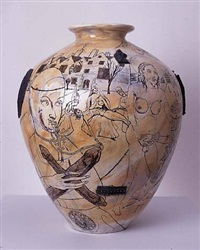

Which is why I came away thinking mostly of deep pockets, and of all the HBS MBA’s who will be adding these things to their collections once the show is over. And there’s a lot of stuff: bronzes, marbles, carved precious stones, gold, and combinations of all of these. It’s additionally reassuring to know all that glitters here really is gold.

That should suggest a wide price range for the various galleries who will carry on the artist’s exercise in ripping off the public by ripping off collectors. But hey, we already know that a lot of collectors want to be ripped off. Otherwise they might worry that they aren’t genuine collectors. Anyone want an Aztec sundial with sea creatures attached?

Almost better than the one in Mexico City’s National Museum of Anthropology:

This is not to suggest that the exhibition(s) doesn’t have its thrilling moments. Who would have thought that an image of Jane Curtin as Connie Conehead

would have made it to the bottom of the Indian Ocean two millennia ago. Cif Amotan II, the freed ex-slave who amassed this treasure before his ship sank, obviously had very eclectic tastes (and was a SNL fan to boot). Mickey Mouse and a lot of other lesser-known characters also make their appearance here, as do a few Jeff Koons-type figures,

and even several Nancy Graves knock-offs (who knew that

Damien Hirst ever heard of Nancy Graves?). But Nancy Graves (1939-95) lived in the olden days, and was just a regular very talented artist working in less opulent materials (see below).

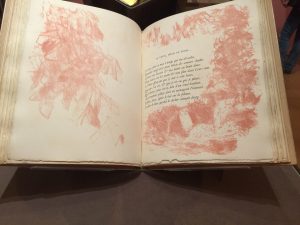

I kept thinking of one of my favorite “expansive” art works: The Marie de Medici 24-picture cycle of paintings at the Louvre, painted for the Luxembourg Palace between 1622 and 1625 by Peter Paul Rubens and (probably) a slew of studio assistants.

Rubens must have run a pretty complex shop to handle some of these big commissions. And he achieved some serious status: raised by Philip IV of Spain to the nobility in 1624, and knighted by Charles I of England in 1630, he even made a lot of money. But Rubens was a obviously piker compared to Damien Hirst!

And always the former museum person, I kept thinking of all the museums that could use this sophisticated and costly technology and installation know-how to enhance the accessibility of their not-fake collections. So many museums for which this expertise would enrich entire communities, not just the privileged art groupies (including yours truly) who trek to the Biennale biennially.

Try to imagine yourself spending a whole evening with your uncle who does nothing but tell corny jokes. You don’t want to be rude and tell him to fuck off, because he’s your uncle. You don’t want to groan and roll your eyes too much, but you can’t help it and you hope his hearing and seeing might not be too great, so he won’t notice. This expensive extravaganza is sort of like that. You get your ticket and you hope that maybe, just maybe, around the corner you’ll discover something new. But you won’t. Good god, Messrs. Hirst and Pinault, at least try to fool me once!

,

,

,

, .

.

.

. I’m not sure you come away from the exhibition with a clear understanding of what this guy was all about, but for sheer visual and technical delight, it’s worth a visit. And you get to experience that great building to boot!

I’m not sure you come away from the exhibition with a clear understanding of what this guy was all about, but for sheer visual and technical delight, it’s worth a visit. And you get to experience that great building to boot!

whom I’ve nominated to play

whom I’ve nominated to play  if they ever make a movie out of the

if they ever make a movie out of the